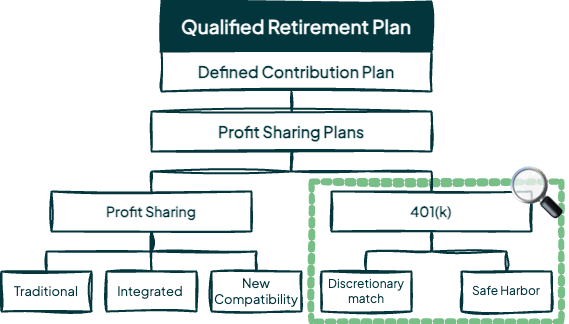

In its simplest form, a 401(k) plan is an employer-sponsored retirement savings plan that allows you (the employee) to contribute a portion of your paycheck into a long-term investment account through automatic payroll deductions. Participating in a 401(k) plan offers numerous benefits, including the potential for your employer to match a portion of your contributions—often serving as a strong incentive to save more for your future. Additionally, 401(k) plans provide distinct tax advantages based on contribution type: Traditional (pre-tax) contributions grow tax-deferred, with taxes payable upon withdrawal, while Roth (after-tax) contributions grow tax-free, provided withdrawals comply with IRS regulations.

In its simplest form, a 401(k) plan is an employer-sponsored retirement savings plan that allows you (the employee) to contribute a portion of your paycheck into a long-term investment account through automatic payroll deductions. Participating in a 401(k) plan offers numerous benefits, including the potential for your employer to match a portion of your contributions—often serving as a strong incentive to save more for your future. Additionally, 401(k) plans provide distinct tax advantages based on contribution type: Traditional (pre-tax) contributions grow tax-deferred, with taxes payable upon withdrawal, while Roth (after-tax) contributions grow tax-free, provided withdrawals comply with IRS regulations.

During your career, you may encounter two primary 401(k) plan structures — discretionary match (where employer contributions vary by policy) and safe harbor (which requires specific contributions to meet IRS nondiscrimination standards) — each designed to suit different employer strategies.

Your 401(k) plan may be a vital element of your future financial security. To optimize its benefits, we encourage you to periodically review your plan’s features and performance. Detailed information is available in the Summary Plan Description (SPD), a document provided to all participants. The SPD outlines critical details, including eligibility requirements, contribution limits, investment options, and vesting schedules – empowering you to make well-informed decisions about your retirement strategy. For questions about the SPD or your 401(k) plan, we invite you to schedule a consultation with us for tailored, expert guidance.

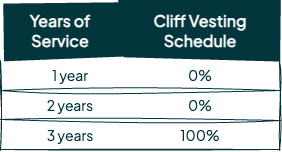

Under cliff vesting, you are 0% vested during an initial service period—typically up to two years—and then become 100% vested on a specific date, often after three years of service. IRS rules cap cliff vesting at three years for employer contributions.

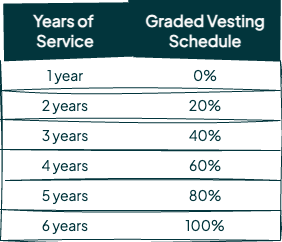

Under cliff vesting, you are 0% vested during an initial service period—typically up to two years—and then become 100% vested on a specific date, often after three years of service. IRS rules cap cliff vesting at three years for employer contributions. Graded vesting incrementally increases your ownership over time, starting at 0% and reaching 100% after six years of service. A common schedule is 20% vesting per year after the first year: 0% after one year, 20% after two, 40% after three, 60% after four, 80% after five, and 100% after six. IRS rules require full vesting by six years for graded schedules.

Graded vesting incrementally increases your ownership over time, starting at 0% and reaching 100% after six years of service. A common schedule is 20% vesting per year after the first year: 0% after one year, 20% after two, 40% after three, 60% after four, 80% after five, and 100% after six. IRS rules require full vesting by six years for graded schedules.