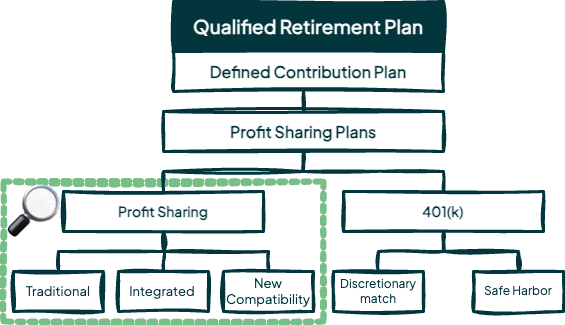

A profit sharing plan is an employer sponsored retirement plan in-which your employer makes contributions (typically based on profits) to an investment account that you will then typically manage for yourself. It is much like a 401(k) plan except you (the employee) don’t make any contributions to the retirement plan. It solely relies upon your employer for contributions. That is not to say a profit sharing plan can’t be combined with a 401(k), because many retirement plans are designed that way, it’s just that a stand alone profit sharing plan relies upon employer contributions only. There are many benefits, both for your employer and yourself, when your company sponsors a profit sharing plan. The contributions your employer makes to a profit sharing plan are generally tax deductible for the company while the contributions rewarded to you (the employee) enjoy tax deferred benefits.

A profit sharing plan is an employer sponsored retirement plan in-which your employer makes contributions (typically based on profits) to an investment account that you will then typically manage for yourself. It is much like a 401(k) plan except you (the employee) don’t make any contributions to the retirement plan. It solely relies upon your employer for contributions. That is not to say a profit sharing plan can’t be combined with a 401(k), because many retirement plans are designed that way, it’s just that a stand alone profit sharing plan relies upon employer contributions only. There are many benefits, both for your employer and yourself, when your company sponsors a profit sharing plan. The contributions your employer makes to a profit sharing plan are generally tax deductible for the company while the contributions rewarded to you (the employee) enjoy tax deferred benefits.

If your employer sponsors a profit sharing plan, you will most likely encounter three various types of allocation methods. The most common ones are traditional (sometimes referred to as pro-rata or comp-to-comp), integrated (sometimes referred to as permitted disparity or social security integration) and new comparability (sometimes referred to as cross-testing). Your employer has discretion on how and when to allocate profit sharing contributions but the one thing they can’t do is discriminate in favor of highly compensated employees. Profit sharing plans must pass a variety of complicated tests to ensure that they do not discriminate.

Your profit sharing plan could be a cornerstone of your financial future. To maximize its benefits, we encourage you to periodically review its features and performance. The Summary Plan Description (SPD), provided to all participants, contains critical details such as eligibility requirements, contribution limits, investment options, and vesting schedules. Familiarizing yourself with these elements empowers you to make strategic decisions about your retirement. For personalized support regarding your SPD or profit sharing plan, we invite you to schedule a consultation for expert, tailored guidance.

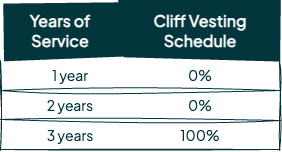

Under cliff vesting, you are 0% vested in employer contributions during an initial period—up to a maximum of three years for profit-sharing plans—then become 100% vested all at once after completing the required service. Some plans may use a shorter cliff, such as two years.

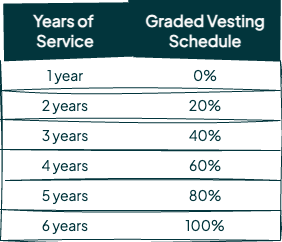

Under cliff vesting, you are 0% vested in employer contributions during an initial period—up to a maximum of three years for profit-sharing plans—then become 100% vested all at once after completing the required service. Some plans may use a shorter cliff, such as two years. Graded vesting increases your ownership incrementally over time. A common schedule starts at 0% in the first year, then adds 20% vesting credit per year of service, reaching 100% after six years. This gradual approach provides a clear path to full ownership.

Graded vesting increases your ownership incrementally over time. A common schedule starts at 0% in the first year, then adds 20% vesting credit per year of service, reaching 100% after six years. This gradual approach provides a clear path to full ownership.